The Algerian Sahara: a journey below sea level

It’s very difficult to write about a trip to the Sahara, such is the uniqueness of the experience. I took my first steps in the Algerian Sahara when I was 10. A trip with my parents, a little adventure that opened the doors to a wilderness where humans have no real place.

A few years ago I decided to go back there for a photo project. If you haven’t gone through the “about us” section, I’m a wildlife photographer and hiking guide. My desire to return to the Sahara was motivated by my love of foxes. And in the deserts of North Africa, there is a particular species of fox, the smallest of the canids: the fennec!

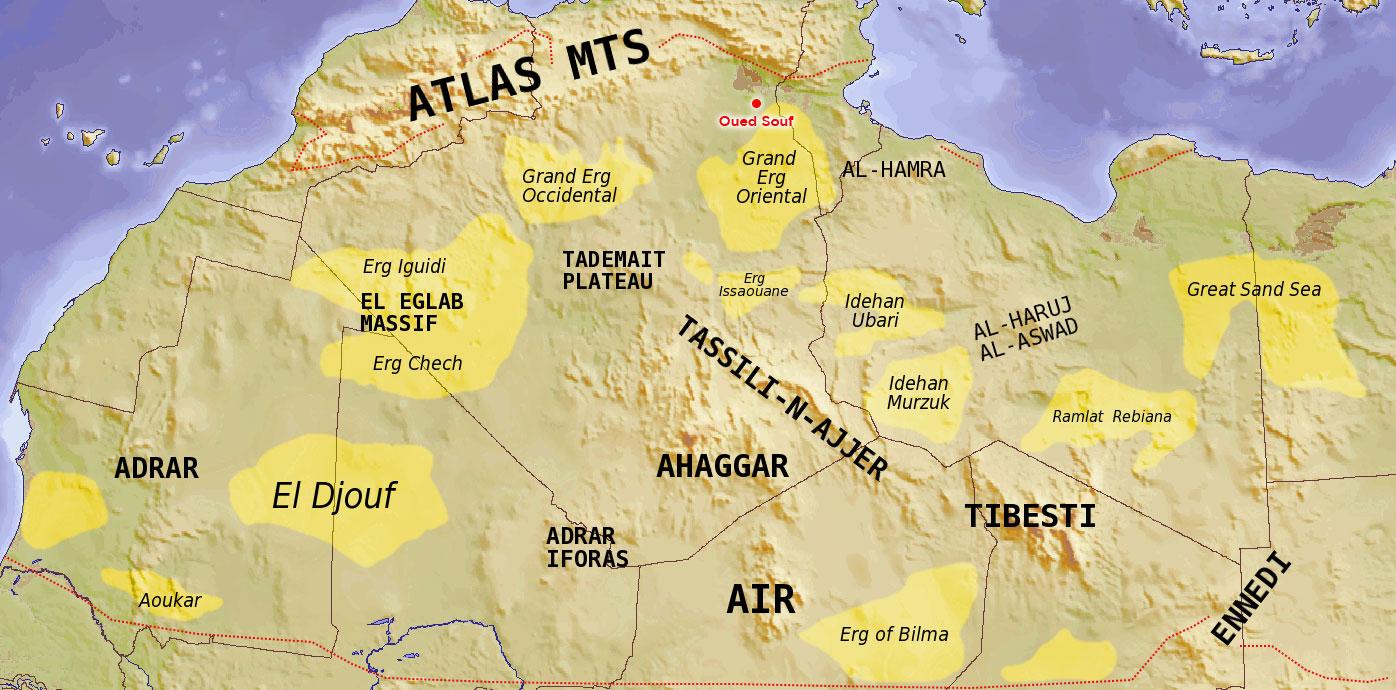

When i was preparing for this trip, I discovered that the Sahara, which we imagine as an immense plain, a flat country, actually has relief. There are hills, mountains and high plateaus at 2000m altitude like in the Tassili n’Ajjer. But above all I discovered that some areas are below sea level. These areas were huge expanses of water and greenery a few millennia ago, when the glaciers of northern Europe melted at the end of the last ice age. Today, everything has dried up and you can walk around at -60m below sea level!

Warning : If you have phobias, be aware that this travel diary contains photos and videos of snakes, scorpions and various insects.

The beginning of the adventure: where to start?

There’s only one way I know of to travel, especially when it comes to my work as a photographer: pack my backpack, get a plane or train ticket and go! But let’s face it, no matter how tough you are, the idea of finding yourself in the middle of the Sahara with no experience, no resources, literally nothing, isn’t very reassuring.

So I started scouring the internet for a starting point, an idea or a meeting to move forward. I finally came across a dissertation on the fennec. A PDF file was my starting point! I Googled the author’s name and found him on Facebook. We chatted, called each other and agreed to meet when I arrive. His name is Lamine.

A perfect host!

Let me tell you the story, because when I arrived, Lamine was waiting for me at the airport. He fed me and put me up even though he knew nothing about me. I can tell you that this hospitality, which I know so well today, blew me away at the time. Lamine and I were very different people. The main thing we had in common was our love of nature. But we spent evenings talking to each other. Our points of view often differed, but at no time did my host take offence. I could stay there as long as I wanted, that was just the way it was, it was normal.

Populations of Algerian Sahara

Amazigh (Berber) ethnic groups

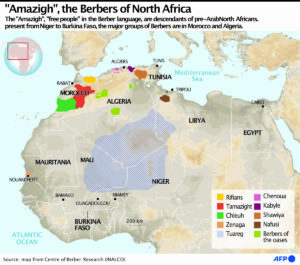

When we think of the Sahara, we think of the Amazigh (Berber) populations, particularly the Tuaregs in Algeria, Libya, Niger and Mali, but there are a large number of ethnic groups with different cultures and languages.

The region I visited is called Oued Souf. The name is a pleonasm, the two words mean the same thing, a river, the first in Arabic, the second in Berber. The population of this region originates from Yemen and speaks exclusively a slang close to Arabic (whereas the slang of the north is a mixture of Arabic, Berber, Turkish and southern European languages). These populations arrived in Algeria recently, around the 14th century, and settled around a river that has now disappeared, hence the name of the region. The area still an oasis, but freshwater is in short supply.

The Amazigh (Berber) ethnic groups of the Sahara

In the desert, the populations are isolated. Around 200km north of Oued Souf, the people are Berbers of the Chaoui ethnic group, so they speak Chaoui. The Mozabites, another Berber ethnic group, live 400km to the west. The south is the kingdom of the Tuaregs, who occupy a vast territory covering four countries (Algeria, Libya, Mali and Niger). Algeria is an incredible country, with a succession of languages, landscapes and cultures.

I’m also lucky enough to speak Arabic, Berber and northern slang. So I can communicate with all the people I meet on my trip to Algeria, whatever their ethnicity.

My first days in a small town in the Sahara?

I arrived at Guemar international airport, a small town lost in the north of the Great Eastern Erg. To get out of town and into the desert, I needed a 4×4 car and someone who knew the desert well. You don’t necessarily think about it, but in the Sahara, it’s not enough for someone to drop you off somewhere, they also have to be able to find you.

So Lamine and I set off in search of a friend of a friend who knows someone who might have a 4×4. Welcome to Algeria: anything is possible here, as long as you believe in it and are patient.

We eventually found Khaled, who agreed to drive me into the desert, and Keddour, who will accompany us to memorise the place. Keddour is a tracker. He knows the desert like the back of his hand and, where you see two similar dunes, he will tell you that he camped in one in 1986 and was nearly bitten by a viper in the other in 1992.

A short visit and a traditional wedding

During these few days of research, I was able to visit the small town of Guemar, its souk, and attend a traditional wedding ceremony. During these ceremonies, men dressed in traditional outfits perform acrobatics while firing their rifles (blanks, I might add). The spectacle was quite impressive (and deafening when the shot was too close).

The Tidjaniya Zaouïa of Guemar

I was also lucky enough to visit the Tidjaniya Zaouïa in Guemar. A Zaouïa is a Koranic school. This one is special in that it was built in 1789, just a few years after the birth of the Tijaniyya Sufi school of Islam. The buildings are made of stone and gypsum to keep them cool, and date palm trunks were used as beams.

During the hottest hours of the day, the town looked a bit like the Algerian Wild West. But at the beginning and end of the day, it was bustling with life, traders were busy, children were coming and going from school, parents were shopping, and some of the shady areas of the town became parks where young people could meet up. I’m always impressed to see these oases where humans have created a living environment in the middle of extreme conditions.

24 hours in the Sahara, the perfect silence!

Living in the Sahara for a few weeks is a very special and unique experience!

We set off in a 4×4 from the town of Guemar at dawn. It was a dry and very pleasant cold. After an hour or so, we left the road and headed into the Sahara through the dunes. I was very excited about the adventure ahead and all my senses were alert. We stopped every now and then to prospect and explore the surroundings before getting back on the road. Our vehicle was a small old Toyota from the 70s and I was amazed at how well it held up. Khaled, our driver, or rather our pilot, managed the terrain perfectly. He knew how to read the sand and avoided the areas where we were likely to get stuck.

After two hours on the road, we stopped at the foot of a hill. The hill was 50m above sea level, while the surrounding area was 40m below. I liked the environment straight away: dunes, rock, lots of rodent and fennec burrows, an area suitable for bivouacking and, above all, a mobile phone network on the hill, in case of problems. I told my companions that this would be my home for a few weeks.

A sand cake, please!

At lunchtime, I was lucky enough to discover how the inhabitants of the Sahara cook under the sand. The technique is simple: they burn a few pieces of dry wood (of which there is no shortage in Oued Souf), place a galette on top and cover the whole thing with sand. This preserves the heat and ensures even cooking. The result is excellent, but it crunches a little under the teeth! 🙂

Leave me alone please!

It was very difficult to explain to the desert people that I was going to be bivouacking for several weeks. In their minds, I was a little madman from the north, who wanted to live in the Sahara alone, without knowing anything about the surroundings. It was difficult to explain to them that I was used to self-sufficiency in extreme regions, that I had studied every point, every constraint and that, of course, I accepted the risk, however small, of an accident or a bad encounter.

I was also well equipped. Equipment that doesn’t exist down there. So I was serene, but I had to redouble my arguments to convince them that they had to leave, and not come back until I phoned them in two or three weeks.

Home sweet home

Let me describe a feeling for you: you arrive in a place where humans are completely absent, and for good reason – the elements are hostile! You decide that from now on, for the moment, for a time, this place is your home. You get to know each other as if you were meeting a new person. But to get to know someone, you don’t ask any questions, you don’t start from any preconceptions, you observe, you open your eyes, ears and nostrils wide. Time slows down considerably. Every second seems to weigh an eternity. Your instincts guide you, your brain registers a vast amount of information.

After a day and two twilights, you wake up from a deep sleep and open your eyes to a place you know.

Within 24 hours, a place that was totally foreign to you becomes more than familiar. You feel reassured, safe, happy, at home! These are the kinds of emotions that my instinct makes me experience every time I settle somewhere, far from civilisation, close to the elements.

Perfect silence or the anguish of townies

Taking up temporary residence in the Sahara, in a completely untamed wilderness, is a multi-faceted experience. On my first trip to the Algerian Sahara, I discovered the true meaning of the word silence. In the absence of objects, buildings, trees or mountains, there is no reverberation. In other words, sound can’t bounce back, it goes away, it disappears. No rivers either, no streams flowing like a presence.

During my first 24 hours alone, in the middle of the dunes, no outside noise, no music, no whispering could distract me from my inner noise. And that’s when the anxiety set in. Imagine hearing everything that’s going on inside you, an unpleasant buzzing in your head, the noise of the city you’ve brought with you, each of your joints creaking at the slightest movement, grains of sand rolling around every time you move, your stomach saying “I’m hungry” or “I’ve eaten too much”, your eardrums clogging up and unclogging as if you were closing an old cupboard door.

But what put me in a state close to panic was that I could clearly hear myself thinking. Every thought was clearly audible. And I discovered that it wasn’t necessary to listen to every thought the brain produced.

Finally, peace!

After 24 hours, my brain calmed down and I gradually began to appreciate real silence! I got used to the noises inside, the buzzing in my head stopped and every nap, every sleep, was the most restful and restorative I’d ever experienced. From that moment on, I enjoyed every second in the Sahara!

Wildlife in the Algerian Sahara

As I explained at the beginning of this travel diary, the reason for my trip to the Algerian Sahara is to discover and document wildlife, and to observe and photograph the smallest of foxes, the fennec.

On arriving in the Sahara, the overriding impression is that no living thing can live in these conditions. Life seems totally absent, with the exception of a few bushes here and there that benefit from the proximity of the water table.

Let’s talk about the water table. I chose to go to an area below sea level for this reason. At -60m below sea level, the groundwater is closer, allowing certain plant species adapted to the environment to survive. And when you think of plants, you think of insects, reptiles, rodents and birds. Predators (mammals and birds) can then move in. In other words, the proximity of the water table creates a food chain and allows adapted fauna to live in this environment.

Animals of the Algerian Sahara

Saharan animals are species that have adapted to this environment over thousands of years. These adaptations essentially concern three aspects: the ability to survive without fresh water, the ability to evacuate heat efficiently and, finally, the ability to survive with a minimum of food. In fact, animals have shrunk in size to limit their energy requirements, have developed heat evacuation systems and obtain all the water they need from their prey, which in turn obtains it from other prey or from plants. In other words, water is always internal to living organisms – it never sees the day light!

The fennec, for example, is three to four times smaller than its cousin the red fox. Its small size means it can make do with very little food. Its oversized ears allow it to evacuate heat quickly. Finally, it obtains all the water it needs from its prey. Insects, for example, are 70% water.

During my travels in the Algerian Sahara, I was lucky enough to observe many species. Birds like the desert traquet, which was my first companion to break the silence. I came across various species of lizard on a daily basis, as well as venomous animals such as the sand viper and scorpions. I narrowly escaped an accident.

Incredibly discreet animals!

There are also some strange animals in the Algerian Sahara, such as the Libyan jird. This medium-sized rodent, which has ermine eyes, has developed some incredible strategies for survival.

First of all, it took me a good week to realise that there was a Libyan jird burrow 30m from my tent. And for good reason, this paranoid little rodent covers its burrow after each entry and exit to avoid viper attacks. Once I’d spotted the burrow, I had to redouble my ingenuity to succeed in camouflaging myself, as the slightest piece of fabric sticking out would cause the Libyan jird to refuse to come out.

Finally, I had to use only silent equipment to take pictures. The Libyan jird was very sensitive to the slightest noise from the shutter release.

Insects 2.0

When it comes to insects, the Algerian Sahara is rich! I was lucky enough to spot the Saharan silver ant (Cataglyphis bombycina), which can survive temperatures of 70°C and sprint at 85cm per second – 108 times the size of its body!

Another curiosity is the Sahara black ant (Cataglyphis fortis). This medium-sized ant uses the position of the sun to find its bearings and has a system similar to a pedometer to measure distances and avoid getting lost. More incredible adaptations!

The Sahara black beetle (Pimelia consobrina) is a very common sight – everywhere, all the time. The smallest piece of food on the ground attracts this medium-sized beetle. I quickly became attached to it. After the flies, it was certainly the insect I came into contact with the most. There were many other species of beetle, most of them black or silver coloured.

The most impressive is certainly the Egyptian predator beetle (Anthia sexmaculata). This imposingly large beetle moves very fast (a little scary, in fact) and has the ability to spit an irritating liquid when it feels threatened.

Vegetation of the Algerian Sahara

I was extremely lucky to experience a rainstorm in the Algerian Sahara. And I was extremely lucky to observe dew in the Sahara. These two rare events are the beginning of everything. They provide the water that will sustain life for several years. This water is immediately consumed by plants and insects. Some of this water reaches the water table, while some evaporates in less than 12 hours. After this time, the Sahara returns to its previous appearance.

Plant adaptations in the Sahara

Like animals, plants in the Sahara have evolved to adapt to extreme drought. On the one hand, they have developed deep root systems capable of finding the slightest drop of water in the deep layers of the soil, and on the other, systems to limit water evaporation. Their leaves are often small and rounded to limit light absorption. In other words, they are the complete opposite of plants in temperate regions, which have large, plant-like leaves.

In the Sahara, some plants produce waxy substances that cover the leaves and limit water loss. Others produce seeds with a watertight shell that increases their lifespan and enables them to hold out until the rains arrive.

As I said earlier, I was lucky enough to experience a rainy day in the Algerian Sahara. But even more incredible was the fact that I was able to witness the flowering and germination of the plants over the following days. In the early hours of the morning, I discovered thousands of seeds that had germinated, plants that had produced flowers at an incredible speed, stems and leaves that had emerged from the sand in less than 24 hours. In extreme regions, in the Sahara as in the Arctic, windows are brief, so vegetation is fast, taking advantage of the slightest opportunity to reproduce and develop.

I experienced this show as a privilege. I witnessed an explosion of life in an environment as arid as the Sahara!

Hostile defence systems

In the Algerian Sahara, the vegetation is also hostile. The leaves and stems of plants are essentially made of thorns and other fairly effective defence systems. In fact, some plants produce thorns that are as hard as metal. I pierced my tent and my inflatable mattress with balls of thorns that clung to my shoes as I walked. These thorns even penetrate the soles of (hard rubber) walking shoes.

A fantastic playground for anyone who loves to explore

The Sahara is an open book. After a sandstorm, the ground is untouched by footprints. It’s the perfect time to start observing what’s going on when your back is turned. I was impressed by the activity of the animals, which was both significant and very discreet. So, within 24 hours, the ground was once again full of footprints that I was quick to read and follow, to understand who had been where, who had attacked whom, who lived where, etc. If you like exploring, then this is the playground for you!

The Sahara, below sea level, is also an exploration ground for materials and other fossils. I was amazed to find shells, for example. All you have to do is pass your hand through the sand to discover vestiges from another era.

Another curiosity is gypsum. This very soft sedimentary rock is formed in salt marshes. And in this region below sea level, salt is everywhere. So I regularly came across formations of varying sizes.

The challenges of bivouacking in the Sahara

I’m used to bivouacking for several weeks at a time. For a photo project, I had to learn to live on my own in the Arctic regions. As a guide, I take groups, particularly to Iceland, far from civilisation for more than 10 days in complete autonomy, in quite difficult conditions. But even so, I wasn’t prepared for what I was going to experience in the Sahara! I’ll tell you about the main difficulties here.

The water!

Obviously, the first problem of bivouacking in the desert is water!

I’m used to long trekking, covering hundreds of kilometres and setting up camps in isolated areas. But in the Algerian Sahara, I had to adapt. The lack of water meant I had to set up a fixed camp to store the dozens of litres of water I needed. Then I explore, returning to the camp in the evening.

Being a rather optimistic person, I took this constraint in a positive way. It allowed me to get to know the areas I was visiting well, to linger over the points of interest and to observe the same animals every day, which is ideal for understanding how nature works.

The lack of water can also be a source of stress, the fear of not having enough. During my first stay, I made a precise estimate of the amount of water I needed and I made sure that I kept to that amount every day. It was an educational experience for me. Living in a world without water makes you aware, in spite of yourself, of what is precious, it marks you, it educates you!

During my stays in the Algerian Sahara, water was used exclusively for food and hydration. In other words, I never washed in the Sahara. I quickly realised that the low level of humidity meant that perspiration was perfectly evacuated. The result is that you never feel dirty, and your clothes don’t stink.

The sand also plays a role in hygiene by trapping grease. All you have to do is dust yourself off to remove both the sand and the grease.

Very low humidity (around 15%)

Les effets du faible taux d’humidité sur la peau

I’ve always lived in regions, by the sea or in the mountains, where humidity levels were quite high. During my travels in the Algerian Sahara, I discovered very low humidity levels, around 15%.

The advantage of such low humidity is that perspiration evaporates instantly. As I explained above, you always feel clean. But there are many disadvantages! Two consequences were particularly distressing for me: firstly, the constant thirst (even after drinking 5 litres of water in a single day), and secondly, the skin drying out!

After a few days in the Sahara, the skin begins to crack, and cracks similar to those caused by eczema appear. These cracks are not painful, unlike the skin that shrinks around the nails. This phenomenon appears after 2 to 3 days and starts to cause pain after a week in the desert.

The feeling of dryness was even worse during the sandstorms. The skin dries out even more quickly. The low humidity, the dust on the skin and the hot wind are a formidable trio for dehydration. I haven’t really found a solution for this problem, apart from drinking water all day.

The sandstorms

I’ve been through quite a few adventures and awkward moments in the wilderness, but I’d put sandstorms at the top of the list of all-time miseries!

Spending several days with sand everywhere, including in your mouth, nose and eyes, and even inside your tent, can drive you mad!

The sandstorms start in March and don’t really stop until midsummer, in July. During my second stay in the Algerian Sahara, which lasted 15 days, I only had two days without a sandstorm. In other words, the desert can quickly turn into hell on earth!

The sandy winds considerably reduce visibility and contribute greatly to dehydration. The sand goes absolutely everywhere. So I gave up trying to find shelter. I experienced these episodes as psychological challenges. The idea, which wasn’t necessarily obvious, was simply to accept, not to fight.

For my photo and video equipment, I had some bin bags in which I put my equipment. Whether in the Sahara or on the beaches, I recommend that you protect your cameras. Sand is formidable for damaging a lens.

Sand is hard on the knees

I recently wrote an article explaining how to train for a trek. As far as the Sahara is concerned, the walk was very hard on the joints, especially the knees. The little extra movement caused by your feet sinking into the sand is not the most comfortable way to walk, and after a few days my body told me so.

I remembered hearing that the best way to walk on sand is barefoot. I can confirm that it works perfectly and is very soothing. But how do you walk barefoot in the middle of snakes and scorpions? So I did it according to the situation. Early in the morning or late in the afternoon, I walked with my shoes on. In the hottest hours, when the venomous animals were holed up, I walked barefoot to rest my joints.

The more physically prepared I was for my trips to the Algerian Sahara, the less discomfort I felt in my joints. Good physical preparation and daily stretching worked very well for me.

Finally, without even realising it, I began to choose where I walk. I avoided the small dunes (where the sand is light) and favoured the small passages where the sand was denser. Exaggerating the relief, I could say that I preferred valleys to mountains.

Watch out for stings and bites

I’m not going to hide it, as much as I love snakes, particularly vipers, I was particularly stressed at the thought of accidentally putting my hand or foot on a scorpion. And in the Oued Souf region, below sea level, the abundance of vegetation, and therefore of insects, has created a favourable breeding ground for scorpions, which are present in great numbers!

In the Sahara, scorpions emerge from their dens at night. In other words, when they can no longer be seen. As well as installing an anti-scorpion barrier around my tent, I’ve made a point of never sitting on the sand in the evening. The one time I did it (I’d gained the confidence…), I withdrew my hand 10cm from a scorpion, the panic was total!

The times I’ve bivouacked in the Algerian Sahara without an anti-scorpion barrier, I’ve used a stick to shake the tent before entering and before leaving. Scorpions are particularly sensitive to vibrations. The best way to protect yourself is to scare them away.

As for snakes, I spent a good month in the Sahara before coming across a sand viper. Its camouflage is such that it is virtually impossible to flush out. In the photo on the left, you can see the viper hiding under the sand. The photo on the right is the one I managed to get once the viper had finished its stalking.

However, I should point out that before I saw it, I put my foot down 30cm away without it moving. Accidents are rare, the viper only attacks if it feels really threatened!

Minor problems

Panneau solaire portable

There are other constraints when bivouacking in the Sahara. For example, it’s very easy to get lost. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to find my way around, and I promise you it’s no mean feat. I got there when I understood how to combine information: position of the sun, relief and details in the environment. Just one of these pieces of information is not enough to get your bearings. For example, I remember getting lost because I turned my head just once!

In fact, I had taken precautions! I’d taken two batteries (powerbank) and a foldable solar panel (I talk about this in my article “Powerbank or solar panels for backpacking?) I also use the OSMAND smartphone app, which allows me to download openstreetmap maps offline and use the GPS to find my way around. As long as I had electricity, everything was fine. So I made sure I never ran out!

What I learned in the Algerian Sahara

The Sahara was the experience of a lifetime for me. These few stays where I lived on my own, far from civilisation, contributed greatly to my education in nature and the essentials.

I discovered that you could live with the bare minimum, in a minimalist environment, without ever getting bored. I realised that boredom comes from cities, from time passing too quickly, from a culture of immediacy. I gave time back its true value and appreciated it for what it was, life, and not for what it allows us to do, consume.

We want everything right away because we’re caught up in a system that doesn’t let us stop, look back or reflect. The Sahara taught me that time can slow down, allowing us to think, to step back.

These trips to the Algerian Sahara also taught me how to manage resources, particularly water. The very fact of understanding where my needs end and wastage begins was a huge step forward for me.

Finally, I took advantage of every moment in the desert to observe life, animals, plants and insects. Discovering the amazing abilities and adaptations of wildlife in this environment has fascinated me and continues to fascinate me!

My next trip to the Algerian Sahara: Djanet, on the Libyan border!

After the Oued Souf, I’m preparing for several trips to the far south-east of Algeria, to the Tassili n’Ajjer cultural park. The park borders Libya and Niger.

The Tassili n’Ajjer is certainly the most fascinating region in Algeria. No fewer than 15,000 rock engravings from various prehistoric periods have been recorded here. Nature here is incredible and wild. This time, the Sahara will not be below sea level but on a plateau 2000m high.

I’ll be sure to tell you all about the adventures to come on The fox diary 😉